Helen’s Plea for Climate Justice before the International Court of Justice (ICJ)

A personal account by Dr Jan Yves Remy [1] (External Counsel for Saint Lucia in the ICJ Advisory Opinion Proceedings)

1. Opening — Why Helen Had to Plead

It is no secret that Saint Lucia, like many other Small Island Developing States (SIDS), is fighting on the frontline of a climate change war we did not start. After all, Saint Lucia contributes just 0.0009% of global anthropogenic (or human-made) greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions (2018)—an insignificant share of the problem. However, like other SIDS, we stand to lose the most. [2]

And in truth, we have been losing this war in reality and in rhetoric. Reality is felt in more ferocious storms, floods and hurricanes, sargassum seaweed invasions, droughts and aquifer salinisation, and the erosion of beaches. If emissions continue to rise, small islands like ours face erasure— being wiped off the map. Rhetoric, through negotiations and advocacy, has not delivered the promised fruit of “1.5 to stay alive”[3]—a slogan crafted by our islands to reflect the maximum temperature increase goals in the Paris Agreement. At the 29th session of the UN Climate Change Conference (COP29), small island states were once again left waiting for the full realization of the commitment to mobilize USD 100 billion per year by 2020 for developing countries[4] —let alone the USD 300 billion pledged annually by 2035 for developing countries, and the USD 1.3 trillion per year by 2035 to be mobilized from a broader range of sources, including private finance. Meanwhile, the existing international finance architecture has deepened our burden: between 2016 and 2020, SIDS paid about 18 times more in debt service than they received in climate finance.[5] The result is a double bind—disaster then debt—for peoples who did not cause this crisis.[6]

Amidst this tale of doom and gloom, there came a fleeting moment of hope—validation, even—of my 2024 decision to serve as External Counsel and represent Saint Lucia before the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in pursuit of an Advisory Opinion on States’ obligations regarding climate change.[7] Specifically, the Court was asked to answer two inter-related legal questions:

- What are the obligations of States under international law to protect the climate system and the environment from anthropogenic GHG emissions for present and future generations?[8]

- What legal consequences arise for States that, through acts or omissions, cause significant harm to the climate system and other parts of the environment, especially regarding SIDS with their inherent vulnerabilities, and people and individuals affected by climate change?[9]

After filing a Written Statement and Written Comments (on 21 March 2024 and 15 August 2024 respectively)[10] and appearing before the Court at the oral hearing at The Hague in the Netherlands (2–13 December 2024)[11], Saint Lucia, and over 100 States and entities participating in the proceedings, finally got an Opinion on 23 July 2025.[12] The Opinion—a careful but consequential clarification of law and responsibility—confirmed that binding international obligations are indeed owed to all States, including SIDS, and to persons and individuals, for climate change; and that legal consequences flow from breach of these obligations.

The Opinion, and proceedings leading to it, offered Saint Lucia a measure of reprieve: they provided a global stage to tell the story of “Helen”—the name we give our island for its natural beauty, reminiscent of Helen of Troy—in our own words. Using a recurring metaphor of the sea, we were able to show how climate change threatens not just our way of life—bleaching our coral reefs, affecting our fishermen’s catch, stripping our beaches of sand, rising to claim our land—but also our history and patrimony. As we explained to the Court, invoking Nobel Laureate Derek Walcott in his poem The Sea is History, the sea holds all of our memories:

…in that grey vault. The sea. The sea

has locked them up. The sea is History.[13]

Participation in the proceedings for the Advisory Opinion represented a defining moment in my professional journey, allowing me to draw on several areas of own expertise in trade, climate and shipping law; as well as in advocacy and litigation. But it was also deeply personal.

In this piece, I provide a personal account of Saint Lucia’s search for climate justice before the ICJ. I trace the chronology of events, outlining our strategies and legal arguments before the Court, as well as the themes we chose to best portray them. As I write, I remain deeply grateful to my fellow legal counsel who were part of the “Team Saint Lucia”; to the staff of the OECS Embassy in Brussels for supporting us at every turn; to our regional brethren and sistren for the faith to walk this journey together; to those unmentioned who assisted in fine-tuning arguments in earlier drafts; to the Government of Saint Lucia, and in particular the Attorney General and Minister of Sustainable Development, for the trust reposed in my abilities; and to Mr Rahym Augustin-Joseph for assistance in an earlier draft of this piece. My deepest gratitude however goes out to the 14 men and women who serve as judges of the ICJ. They restored my faith in the justice of our cause, and bravely played their part in solving a global problem which, in their own words:

2. The Calling of Helen — Why Saint Lucia Joined

When I have been asked why I agreed to represent Saint Lucia, I can only offer a complex disjointed answer.

One strong feeling that compelled me from the very beginning was a growing sense of powerlessness; a sobering feeling that, with all we had done as a country, with our limited capabilities, to contribute to solving the problem of climate change, it still was not enough, and others with greater responsibility and capacity were not doing their parts. As we would set out clearly in our Written Statement, Saint Lucia has played an outsized role: we are parties to all of the international climate treaties – the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), the Kyoto Protocol, and Paris Agreement; we recently introduced our first Climate Change Bill in Parliament, submitted National Communications, and updated Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) under the Paris Agreement.[15] Our then Minister James Fletcher even participated as a member of the ministerial team at COP21 where the Paris Agreement was adopted.[16]

Under the maritime regime, Saint Lucia is a party to UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, and has signed the newest BBNJ Agreement.[17] Saint Lucia is also a member of COSIS, the inter-governmental body created in 2021 to promote and develop rules of international law on climate change, and which requested an advisory opinion a Tribunal (ITLOS) on obligations under UNCLOS concerning the impacts of GHG emissions on the marine environment.[18] (Its Opinion (May 2024) would later reinforce many of the arguments we made before the ICJ.)

Our musicians and artists have raised awareness of climate change impacts, through campaigns such as “1.5 to Stay Alive”; our poets and writers have produced iconic work highlighting the existential risks to SIDS.

Against this backdrop, when the Attorney General invited me to lead Saint Lucia’s participation in the Advisory proceedings, I accepted. Alongside Saint Lucian legal counsel—Mrs. Rochelle John-Charles (AG’s Chambers) and Ms. Kate Wilson (Ministry of Sustainable Development)—we formed a compact, purpose-built three-woman team. Our participation was not choreographed years in advance; it was a response to a last-minute regional stirring and a personal call to action by Dr. Justin Sobion, a Trinidadian by birth and a former law classmate of mine, working in the Pacific, who had reached out to me personally to help motivate broader Caribbean participation.

Once Saint Lucia had decided to join the proceedings, we met other like-minded CARICOM States at a regional “writeshop” held in Grenada in February 2024. There, supported by Vanuatu’s legal counsel—Prof. Margareta Wewerinke-Singh and Ms. Lee-Ann Sackett (to whom we are eternally grateful)—we understood the key role that the Pacific SIDS—and in particular Vanuatu—had played in championing the request to the UN General Assembly, which had then forwarded the request for an Advisory Opinion to the Court. At the writeshop, we also learned about our own regional realities and capabilities, and, guided by Caribbean scientists, climate advocates, international lawyers, and youth advocates, we framed an approach: blending science, law, and lived realities into submissions that were regionally rooted. We soon realized that, even if an Advisory Opinion by the Court was not like a normal dispute and would not be binding in its effect, it would clarify the law for all States, shaping climate negotiations, guiding domestic action, and possibly even preparing the ground for future litigation. That understanding began to open up possibilities for us on how we might use these proceedings to our advantage.

3. Our First Written Statement — Strategy, Science, and the Law

With a short period of time to draft – in fact less than a month – we knew we had to be strategic. With more than 100 States and entities were participating in the proceedings (a historic number for the ICJ), numerous legal instruments and norms that were potentially relevant to the first question, and decades of ICJ jurisprudence (I had not studied ICJ case law since leaving law school over 25 years ago), the terrain to cover was vast.

Our posture was simple: lead with science, make it personal, and argue the law holistically—with the realities of SIDS as the emphasis and through-line. It was our opportunity to “school” the world on SIDS, and Saint Lucia in particular: from our geographical positioning; to our geo-economic and political role in the global climate conversation; to our economic vulnerabilities; and finally, to the legal framing that underpins our claims for special treatment in various international legal frameworks.

1) Begin with Science then Make it Lived and Local

We anchored our submission in climate science. At the Grenada writeshop, Caribbean scientists serving on the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) – considered to be the “best available science” – had helped to distil the materials from recent IPCC reports that were most relevant to SIDS. We submitted these excerpts as an Annex to our Written Statement, paired with Saint Lucia’s own assessments — the First Biennial Update Report (September 2021), the National Adaptation Plan (2018–2028), and the 2006 and 2015 State of the Environment Reports.

Together, these reports demonstrated that the scientific community had agreed, by consensus that human activities, specifically anthropogenic GHGs, are causing harm to the climate system; and that present and future risks – sea level rise, extreme droughts, tropical cyclones, coral reef damage – pose significant challenges for the Caribbean threatening sustainable development.[19] For Saint Lucia, we itemized the impacts by sector and people, highlighting in particular water resources, agriculture, fishers, tourism and coastal infrastructure, and at the human level, on women and vulnerable groups.[20]

A theme we returned to repeatedly — because it is existential — was sea level rise. We spelled out how rising seas threaten Anse La Raye, Canaries, and Dennery, risking the loss of fishing utilities, community infrastructure, and cultural space. We framed the ocean as both memory and market — the place where our children learn to swim, and where our fishers earn their keep.[21]

2) Identifying the Obligations Owned Comprehensive without Being Sprawling

In answering the first question – what are the obligations owed by States to each other as well as present and future generations – we focused on a defined set of obligations and principles, without pretending to be exhaustive.

We decided to start with the obvious – the climate treaties, including the UNFCCC and Paris Agreement as the backbone, with the principle of Common But Differentiated Responsibilities and Respective Capabilities (CBDR-RC) as the foundation.[22] That principle, we reminded the Court, is key to understanding what duties are owed to SIDS that historically and currently make no contribution to climate change, and which have least resources to address its impacts. We emphasized that, far from just imposing procedural and non-binding obligations – for instance to prepare and implement nationally-determined contributions (NDCs) and aspire to meet temperature goals based on the best available science – these treaties are binding and not merely aspirational. We submitted an Annex with a full list of provisions that name or prioritize SIDS, as well as articulate the duties on developed States to comply with their obligations of mitigation and adaptation, and in particular provide finance, technology, and capacity-building to prevent and deal with the consequences of climate change.[23]

In addition to the climate treaties, we also referenced unwritten rules of customary international law—mindful of concerns among some SIDS that these rules might be portrayed as softer and more discretionary than they truly are, and therefore displaced by obligations that many developed countries considered more relevant but which were ultimately less stringent. We highlighted in particular the duties to prevent significant transboundary harm and to cooperate as customary anchors applying to both the atmosphere and the high seas. We framed these as obligations of stringent due diligence, requiring States to use all appropriate means available to them, proportionate to the level of risk, the timeframe, and their capabilities.[24]

Finally, we turned once again to the sea. We reminded that Court that Saint Lucia is a member of COSIS, which had brought a similar request before the Tribunal on the Law of the Sea (ITLOS).[25] We asked the Court to read its provisions, especially Articles 192-194, in light of contemporary science, recognizing GHG emissions as “pollution of the marine environment.” With that framing, the UNCLOS duties to prevent, reduce, and control pollution became directly relevant to climate conduct.[26] We flagged the pending ITLOS Advisory Opinion (delivered May 2024), which we expected to endorse this approach.

In interpreting all of these rules and norms, we urged the Court to apply the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties interpretive principles[27] — a context-sensitive, teleological reading consistent with the object and purpose of the various Agreements. We emphasized “systemic integration”: the need for the Court to read the relevant climate treaties together with the UN Charter, UNCLOS, customary law, and human rights, rather than in silos.[28] We cited the International Law Commission’s work on Protection of the Atmosphere, which cautions against fragmentation and highlights the salience of vulnerable groups, including SIDS.[29]

3) Legal Consequences — “Then What?”

Saint Lucia also addressed the second part of the Court’s question: what legal consequences follow from the breach of any obligations found to apply?

We grounded our answer in the ILC Articles on State Responsibility (ARSIWA), and pointed the Court to its own environmental jurisprudence on how remedies operate in environmental harm cases.[30] Under these rules, we argued that breaches of climate obligations trigger obligations to continue performing all obligations under international law; to cease any continuing unlawful acts; to offer assurances and guarantees of non-repetition; to and provide full reparation for injury caused by the wrongful act — through restitution, compensation, and satisfaction. We sought to catalogue the real-world application of these rules in our regional context: restitution should mean reducing emissions (per UNFCCC/Paris Agreement and NDCs), and providing support to our islands (finance, capacity building, technology transfer); compensation should encompass ongoing harm, including financing for the Loss and Damage Fund that Caribbean countries have supported; and satisfaction might take the form of acknowledgment, apology, or expression of regret for those most responsible for causing climate change[31], which we linked to the Caribbean’s demands for reparatory justice. Quoting Saint Lucian Ambassador Dr June Soomer, the UN Permanent Forum for People of African Descent, we argued that:

4) Filing the Written Statement with the Court

Once written, double-checked, and reviewed, the next task was to file our Written Statement physically with the ICJ’s Registrar in The Hague, the Netherlands. Coordinating with other participating OECS States (Saint Vincent and the Grenadines and Grenada), we entrusted that responsibility to our OECS Mission in Brussels, led by Chargé d’Affaires Desmond Simon (Saint Lucia) and Ambassador Joseph (Grenada). They worked diligently through the night to prepare hundreds of pages of submissions and annexes, ensuring they were delivered on time.

Even though we were not physically present for the filing, the submission of the OECS countries’ pleadings was a moment of immense pride—for our team, our country, and our region.

4. Sharpening Our Arguments — The Written Comments (August 2024)

A few months after we had filed Saint Lucia’s Written Statement, the Court invited delegations to provide Written Comments on each other’s Written Statements. While the prospect of reading through thousands of pages of legal arguments and claims, in limited time, was daunting, we decided to engage. In the end, responding to the Written Comments proved a godsend: they forced us to examine others’ submissions and gave us a sense of where disagreements were coalescing, where arguments needed strengthening, and where new ones had to be made.

By now, we had developed an easy rapport with our OECS colleagues in SVG and Grenada, and other CARICOM colleagues. Working with them, and supported by Vanuatu’s counsel, we shared summaries and analyses of the broader field of submissions. These “cheat sheets” provided a bird’s-eye view of where the major powers were landing.

Unsurprisingly, a stark divide emerged clearly. Historical polluters – mainly developed countries – were pushing hard against any finding of legal responsibility, arguing that the climate treaties created only “soft” obligations and/or that attribution of blame for climate change among states was not scientifically possible or legally necessary. Some newly industrialized States resisted too, arguing that the principle of CBDR-RC meant that only historical polluters should be liable for any of the damage caused by climate change. Many developed countries also sought to avoid any legal consequences for breach, and rejected ARSIWA’s applicability. By contrast, SIDS’ factual and legal claims derived from our special circumstances were rarely contested — even though the logical consequences – acceptance of some sort of liability – were.

With the battle lines drawn, we decided to only engage on specific areas of contestation, resuling in Written Comments that were shorter, crisper, and aimed at reinforcing core points. We focused on five main lines of argument.

First, we reminded the Court of its role was to clarify obligations – not defer to politics – and that the ICJ’s interpretive authority mattered precisely because other regimes — UNFCCC, Paris, UNCLOS, human rights law — were each grappling with climate change.[33]

Second, and drawing heavily on the framing and arguments advanced by Vanuatu, we challenged the claim that there was no “relevant conduct” that could be identified as wrongful, or that responsibility for climate change could not be attributed to the actions of individual States or groups of States.[34]

Third, and by this time, in August 2024, ITLOS had delivered its Advisory Opinion in the COSIS case. That Tribunal, seized of similar issues, had confirmed that GHG emissions fall within UNCLOS obligations to prevent, reduce, and control marine pollution, that States owe due diligence, and that special consideration must be given to SIDS. We urged the ICJ to follow this reasoning and apply it more broadly.[35]

Fourth, we pushed back hard against arguments that the climate treaties are lex specialis that displaced custom or human rights.[36] Instead, we stressed systemic integration: climate treaties reinforce, not replace, general international law. We argued that human rights — to life, health, culture, and a healthy environment — remain relevant, as acknowledged in the Paris Agreement’s Preamble.

Fifth, we reinforced the principle of CBDR-RC, and the differentiated responsibilities of States. We linked this not only to mitigation but to finance, technology transfer, and capacity building — obligations repeatedly affirmed in UNFCCC and Paris texts.[37]

On the question of the legal consequences, we supplemented our earlier reliance on ARSIWA with greater detail.[38] We argued, like others in CARICOM, that full monetary reparation was owed for climate harms. This could include contributions to funds (Loss and Damage, Green Climate Fund), as well as obligations of technology transfer. We pointed to fossil fuel subsidies, estimated by the IMF at USD 7 trillion in 2022,[39] as evidence that States had resources but chose to perpetuate harm.

We also contextualized remedies within lived realities. For instance, Grenada and Saint Vincent and the Grenadines pointed to Hurricane Beryl, which had just struck in the time between the Written Statement and Comments, as an example of rapid-onset destruction requiring immediate finance and adaptation support.[40] We added that displacement and migration caused by climate change must be recognized as legal consequences.

Though our Written Comments were modest in length, they played a vital role. They showed solidarity with other CARICOM States and other SIDS, whose submissions we cited, integrated ITLOS’ fresh authority, and underlined that climate law is not a closed system but part of the larger corpus juris. They also made clear that remedies must be real: not charity, but justice.

5. Showtime — Oral Pleadings (The Hague, December 2024)

The public hearings for the Climate Change Advisory Opinion were held from 2–13 December 2024 in the Great Hall of Justice at the Peace Palace in The Hague. For those of us who work in international law, the Peace Palace stirs a deep sense of history and purpose; and the significance of this moment in my career was not lost on me.

Saint Lucia was one of nine CARICOM delegations to participate in the oral phase of the Advisory proceedings—Jamaica and Dominica having joined the proceedings only at this final stage. We were glad for the added numbers which would allow us to better execute the strategy we had agreed coming out of the November “advocacy” workshop in Barbados to prepare for this phase. The workshop, hosted at the Cave Hill Campus by UWI’s Faculty of Law (Prof. David Berry), myself (as Director of the SRC), and Dr. Justin Sobion, focused on a few core themes and legal arguments for each country to refine. At the same time, it encouraged us to draw on the lived experiences of the islands—especially recent disasters such as floods and hurricanes—to tell our story in different ways. We were also coached on posture and demeanor before the Court by experienced regional and international practitioners, and again supported by lawyers from Vanuatu. A memorable feature of the advocacy clinic was a session on the importance of “storytelling” in court—showing that what resonates is not only legal argument, but also narrative.

Armed with that guidance, our three-woman legal team set about preparing for the oral proceedings and devised a strategy shaped by both chance and choice. We worked diligently—meeting online and at the Ministry of Sustainable Development to draft, refine, and fine-tune our arguments, and to divide the presentations among us. Our goal was maximum impact—using imagery and storytelling while taking full advantage of our speaking slot: last on the day, immediately after the United Kingdom. This positioning allowed us not only to respond directly to the UK’s arguments, but also to close that day’s session with dramatic effect.

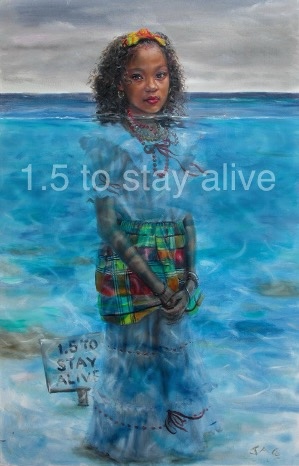

Inspired by the theme of storytelling, we chose a painting by Saint Lucian-based artist Jonathan Gladding, depicting a young girl submerged in water—whom we called Helen—to project on the courtroom screens. We also drew on Derek Walcott’s poetry, using his piece The Sea is History to connect the sea that holds our memories with the same sea that now threatens to submerge our country and our child, Helen, under the rising tides. The image became the quiet refrain of our case.

We arrived at the Hague, a few days before our scheduled appearance. The Carlton Hotel became our temporary headquarters, close enough to the Peace Palace for last-minute rehearsals and place for friends from the Caribbean, OACPS, AOSIS, and other SIDS delegations. The OECS Embassy team from Brussels also travelled to The Hague and provided support throughout.

1) Our Appearance before the ICJ

On 10 December 2024, Chargé d’Affaires Desmond Simon introduced our delegation. The image of Helen appeared on the courtroom screens, returning at each transition.

I opened. Wearing a rose madras corset over a black suit — a small, stubborn reminder of who we are — I began by introducing Helen and reminding the Court that this was Saint Lucia’s first appearance before the ICJ. We came not as spectators but as a large ocean State asking the Court to read the law where we live — in the sea, on the coast, in the markets and schools the ocean frames. I invoked my father’s village, Laborie, and the sea where he bathed as a boy — an ordinary memory now threatened by climate change. I urged the Court to speak in plain terms, because our destiny is interwoven with the fabric of humanity. I placed the science and Saint Lucia’s national evidence (Biennial Update Report, National Adaptation Plan, State of the Environment) squarely in front of the judges, to show scale, pace, and disproportionate vulnerability.

Ms Kate Wilson followed. She turned immediately to the legal architecture, taking square aim at the UK’s argument that climate treaties are the only lex specialis that matters, and that their “softness” should deter the Court from drawing harder lines. She countered that the UNFCCC and Paris Agreement bind States; they do not displace customary law. She stressed that the duty to prevent significant transboundary harm and the duty to cooperate remain in full force, reinforced by UNCLOS Article 194 on marine pollution. She also mentioned as applicable obligations contained in human rights treaties, including the right to a healthy environment referenced in the Paris Agreement’s Preamble, and the ongoing work being done through regional human rights treaties, like the Escazu Agreement. She pressed the Court to adopt the systemic integration we had argued in writing, reminding it that States owe stringent due diligence — all appropriate means, commensurate with risk, time horizons, and capabilities.

Finally, Rochelle John Charles brought us home to consequences. She asked the Court to confirm the ARSIWA sequence — continue performing, cease wrongful acts, guarantee non-repetition, repair — and then translated these principles into a small island context. That meant ecosystem restoration (corals and mangroves), protection of coastal communities (Anse La Raye, Canaries, Dennery), water security, and early warning systems. It meant finance, technology, and capacity consistent with treaty obligations. And it meant ending contradictory policies, such as harmful fossil fuel subsidies. She connected these remedies to regional initiatives, especially the Bridgetown Initiative that proposes reform to the international finance architecture, noting that a remedy unfunded is a remedy unfelt.

The Aftermath

When we finished — last on the day — people we had never met stopped us in the corridor, congratulating us. It seems our strategy and attention to detail worked, because after our performance[41], Saint Lucia’s pleading was described as the “Taylor Swift concert of international law”[42], breaking the monotony of courtroom discourse with colour, passion, and clarity. One participant even told me, “I wanted to be Saint Lucian after I heard you all.”

We took pictures with other delegations, thanked the Court staff, and walked out of the Peace Palace gates into the December cold with something I had not had before: the settled sense that we had done our best and had made Saint Lucia visible in a chamber where it had never stood.

6. The Court gives its Advisory Opinion (23 July 2025) — Did We Win?

I remember exactly where I was when the President of the Court, Justice Iwasawa began to read the Advisory Opinion of the Court on 23 July 2025 — a mere seven months after oral pleadings. Swift by any measure of international dispute settlement, it was still enough time for us to steel ourselves for caution. And indeed, the tone was cautious. But the substance — 133 pages of it — was quietly decisive.[43]

We had been warned to expect restraint. Instead, we heard a Court that largely accepted our frame: read the whole house of international law together; let customary duties of prevention and cooperation do the heavy lifting; treat the UNFCCC and Paris Agreement as binding in content and ambition; and keep State responsibility (ARSIWA) on the table. Where the Court hesitated was on SIDS-specific consequences and the granular finance “bite” we had pressed. What follows is how the holdings map against what we argued in the Written Statement, sharpened in the Written Comments, and staged at The Hague — with Helen’s thread running through it all.

1) Method and Scope — A Whole House, Not a Silo

From the start we had urged the Court not to box itself into the climate treaties. Reading the scope of applicable obligations broadly, we had argued that the climate treaties, UNFCCC/Kyoto/Paris, UNCLOS, human rights, and customary environmental law were all relevant. The Court agreed. It adopted systemic integration as method, guided by the Vienna Convention interpretative principles of good faith, objective and purpose, and effectiveness.

Most powerfully, the Court emphasized that all fields of international law are implicated in the protection of the climate system — and was clear that other areas of law, including trade, investment, and finance were not excluded[44] — music to my ears as a strong advocate of trade law. It even mentioned the discussions at the International Maritime Organization – a field that I also have taken up and where SIDS are part of discussions on maritime decarbonization under a proposed “Net Zero Framework”.[45] It was a vindication of the broader vision we pressed: that climate change is not a silo, but a condition that runs through the full corpus juris. The Court also situated its reasoning in dialogue with other tribunals, citing ITLOS and the Inter-American Court, ensuring coherence across fora.[46]

2) Science and Humanity — The IPCC as Anchor

3) Treaty Obligations — Hard Law, Not Aspirations

On the treaties, the Court grouped duties as we did: it found that relevant obligations of mitigation, adaptation, and cooperation (finance, technology, capacity) applied. It read them as legal obligations borne by stringent due diligence, contextualized by COP decisions and practice.[48] Crucially, the Court rejected the view that open-textured language in the UNFCCC and Paris Agreements (“take full account”, “give full consideration”) reduces the provisions to mere aspirations.

This was vindication of our Annex II argument that provisions concerning SIDS and LDCs (UNFCCC Arts 4.4–4.8; Paris Art 2.2 and Preamble) have legal content. The Court agreed in principle. Where it was more cautious — as we feared — was on the specific obligations relating to finance and capacity building: while affirming support in finance and technology are an obligation but left the quantum and channels to politics and in concreto cases.

4) Customary Law and UNCLOS — Prevention, Due Diligence, and Cooperation

A key pillar of the Opinion is customary law and the principles it embodies—such as the duty of prevention, which requires a stringent due diligence obligation to avoid significant transboundary harm. This duty is operationalized through domestic regulation, environmental impact assessments, notification, consultation, and cooperation. Here again, the Court echoed our framing.

Importantly, the Court linked these obligations to the obligation to the marine environment via UNCLOS. It cited Article 206 (EIAs) and Article 194 (pollution prevention), holding that GHG emissions fall within their scope. It instructed States to “cross-read” UNCLOS and Paris obligations — systemic integration in action.

ITLOS’s May 2024 Advisory Opinion was referenced and validated. The ICJ drew on ITLOS’ articulation of due diligence, precaution, and special consideration for SIDS in interpreting UNCLOS. Interestingly, it was unencumbered in its reliance on that case law – advancing the coherent approach to international law especially on the topic of climate change. It was also confirmation that our regional effort — joining COSIS and building the law of the sea case — mattered.

5) Attribution, Conduct, and Causation

Here lies one of the Opinion’s most consequential moves. The Court clarified that attribution follows established rules of international law, and that “relevant conduct” is not limited to direct emissions. It includes licensing, permitting, and subsidising fossil fuel activities.[49] In other words, States cannot insulate themselves by pointing to private actors; they are responsible where they fail to regulate or supervise them – a far-reaching finding in terms of which types of activities, beyond just state actors, are implicated.

On causation, the Court was nuanced. It did not require pinpoint attribution to one State. Instead, it recognized that in a global harm situation like climate change, causation can be established through contribution to risk and harm, taken together. This reflects exactly what we and other SIDS argued: that collective conduct can ground legal responsibility, even if individual shares vary. It leaves the door open for future in concreto claims to establish liability on the basis of contribution, not dominance.

6) State Responsibility and Legal Consequences

Another important finding of the Court – as we had argued – is that the rules on State Responsibility – ARSIWA – apply. The Court confirmed that the climate treaties are not self-contained, and that breaches of treaty and custom alike trigger the consequences of State responsibility: continued performance, cessation, guarantees of non-repetition, and reparation.

Here the Court invoked obligations erga omnes — duties owed to the international community as a whole. Protecting the climate system, the Court said, is an obligation erga omnes, meaning that all States have a legal interest in compliance, whether or not directly injured.[50] This was a breakthrough: it means SIDS need not stand alone; any State can invoke these obligations in future proceedings.

On reparation, the Court stopped short of fixing liability or specifying finance quantum. It left those for politics and specific cases. But it confirmed that reparation — restitution, compensation, satisfaction — applies, and that existing finance mechanisms do not preclude responsibility. They are cooperative pathways, not liability shields.

7) What It Did Not Say — SIDS and Obligations owed

For SIDS, the Opinion is both vindication and frustration. It hardened obligations we care about — Paris as binding, CBDR-RC as interpretive thread, UNCLOS duties applied to GHGs, prevention and cooperation as custom, erga omnes standing, and attribution rules that encompass subsidies and licensing. But it did not name SIDS specifically, nor did it give the granular finance consequences we had sought.

Sea level rise, existential threats, and vulnerabilities were present through the Opinion’s reliance on IPCC science. Our arguments lived between the lines. It would have been satisfying to see “Helen” herself mentioned, but recognition came indirectly in Judge Charlesworth’s Separate Opinion. She chose to dwell on the imagery offered by SIDS and climate-vulnerable groups, citing the testimony of a Pacific I-Kiribati villager describing how his community had become “scattered, broken” after relocation, the story of women walking further and further inland to fetch freshwater as saltwater poisoned their wells, children suffering malnutrition, women losing traditional craft materials, and disabled people in Tuvalu unable to reach safety during floods.[51]

For her, these were not rhetorical flourishes but evidence of how law must be interpreted through lived experience. That acknowledgment matters. Even if the Court as a whole stopped short of naming SIDS, a judge of its bench validated the imagery and voices that we and our peers had brought. It was a recognition — if only indirect — that our stories belong to the law.

8) A Court Within Its Limits

The Court also reflected on its own place. It emphasized that its role was limited—that it would not legislate finance or overstep into political bargains. It explained that:

This was the Court’s way of answering our plea without overreaching. It set the legal scaffolding and left the building for us to complete. Its approach in general reminds me very much of some of the early case law of the ECJ and the Caribbean Court of Justice when they were just establishing their authority—forceful in articulating obligations, but more restrained in specifying legal consequences. As creatures of international (and political) processes, they understand all too well that, in the final analysis, it is States that remain the primary objects of the law.

7. My Closing Reflections

So did we really win?

Judged by the main thrust of the Court’s Opinion, I would certainly say that we won this battle. The Court gave us more than we expected, even if less than we hoped. For SIDS, it crystallized our core arguments: obligations are binding; prevention and cooperation are customary duties; UNCLOS applies; ARSIWA remains available; obligations are erga omnes; and attribution rules capture conduct we had highlighted, such as fossil fuel subsidies. It did not name us directly, but it wrote our survival into the law’s logic. Like Helen herself, our arguments were present even when unspoken. And like Helen, we endure.

But it is harder to say whether we have won the war. As lawyers, we will put these arguments to maximum effect in the various theatres of ongoing negotiations—whether at the WTO, where we seek to strengthen climate-related arguments, or in efforts to reform fossil fuel subsidies; in the IMO, where we press for greater representation of SIDS; at COP30, where we will demand more robust support for finance-related obligations; or in the broader push for reform of international financial institutions and debt rules that currently weigh heavily on countries being asked to shoulder the costs of adaptation. Even domestically, the Opinion will inform how we prepare the next cycle of NDCs and how governments allocate climate and ODA budgets.

The real test lies beyond law and negotiating theatres – it will lie in whether it can change hearts and minds, and ultimately behaviours. Will this decision prick the conscience of decision makers—or of the citizens they serve? Will it make one more politician pause when a scientist speaks? Will it influence the decision to direct more resources to countries and causes that may not seem immediately relevant, but could save a home, a life, or even the future of someone far away—or indeed, the lives of their own children, who five or ten years from now may ask why their leaders and people did not do more?

As for me, the Opinion marked the culmination of a journey. It reminded me that, even as I remain a tiny cog in a big wheel, I can use my voice, my determination, and my skills to advance the needs of my country, my region, and humanity. It offered the rare opportunity to make Saint Lucia visible in the world’s highest court, and to leave a record that our island, and SIDS everywhere, were not silent in the face of the rising sea.

[1] Dr Jan Yves Remy currently serves as the Director of the Shridath Ramphal Centre for International Trade Law, Policy and Services, at the UWI, Cave Hill Campus

[2] UNFCCC Secretariat, National Greenhouse Gas Inventory Data 2018.

[3] Paris Agreement (2015) UN Doc FCCC/CP/2015/10/Add.1, Art 2(1)(a).

[4] Copenhagen Accord (2009) UN Doc FCCC/CP/2009/11/Add.1.

[5] Saint Lucia, Written Statement paras 21–24, and Saint Lucia Oral Statement (ICJ, 10 December 2024)

[6] ibid paras 2–4.

[7] UNGA Res 77/276 (29 March 2023) UN Doc A/RES/77/276.

[8] ICJ, Request for Advisory Opinion on Obligations of States in respect of Climate Change (2023).

[9] Saint Lucia, Written Comments (ICJ, 15 August 2024).

[10] ICJ, Oral Pleadings, 2–13 December 2024, CR 2024/xx.

[11] ICJ, Advisory Opinion on Obligations of States in respect of Climate Change (23 July 2025) (ICJ Advisory Opinion).

[12] Derek Walcott, The Sea is History (1979).

[13] ICJ Advisory Opinion, para 615.

[14] Saint Lucia, Written Statement, Sections III–V.

[15] UNCLOS (1982) 1833 UNTS 3; Agreement on Biodiversity Beyond National Jurisdiction (2023).

[16] Saint Lucia, Written Statement, para. 51.

[17] ITLOS, Request for Advisory Opinion submitted by COSIS (21 May 2024).

[18] Saint Lucia, Written Statement, paras 45–51.

[19] Saint Lucia, Written Statement, paras. 18-19.

[20] Saint Lucia, Written Statement, paras. 25-35.

[21] UNFCCC (1992) 1771 UNTS 107; Kyoto Protocol (1997) 2303 UNTS 162; Paris Agreement (2015).

[22] Saint Lucia, Written Statement, Annex II.

[23] Saint Lucia, Written Statement, paras. 49-65.

[24] Saint Lucia, Written Statement, paras. 66-68; 75-78.

[25] ITLOS, COSIS Request for an Advisory Opinion.

[26] Saint Lucia, Written Statement, paras. 69-74.

[27] Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties (1969) 1155 UNTS 331, Arts 31–33.

[28] Saint Lucia, Written Statement, paras. 38-40.

[29] Saint Lucia, Written Statement, paras. 41-42

[30] Saint Lucia, Written Statement, paras. 81-95, referring to ARSIWA ibid Arts 29–37.

[31] Ambassador Dr. June Soomer, Statement to the UN Permanent Forum on People of African Descent (2023).

[32] Saint Lucia, Written Statement, para. 93.

[33] Saint Lucia, Written Comments, paras. 10-14.

[34] Saint Lucia, Written Comments, paras. 15-20.

[35] See Saint Lucia, Written Comments, paras. 5, 13, 28.

[36] Saint Lucia, Written Comments, paras. 21-26.

[37] Saint Lucia, Written Comments, para. 27

[38] Saint Lucia, Written Comments, paras. 38-43.

[39] IMF, World Energy Outlook: Fossil Fuel Subsidies (2022).

[40] Saint Lucia, Written Comments, paras. 38-40 ( referring to arguments by Grenada, SVG)

[41]

[42] See Daily report for 10 December 2024, International Court of Justice Hearings on the Obligations of States in Respect of Climate Change, Earth Negotiations Bulletin (ENB): available at https://enb.iisd.org/international-court-justice-climate-daily-report-10dec2024

[43] ICJ Advisory Opinion, paras 352–355 (UNCLOS obligations; systemic integration).

[44] Ibid, para. 173.

[45] Ibid, para. 367.

[46] ibid paras 145–151; Inter-American Court of Human Rights, Advisory Opinion on Climate and Human Rights (2023).

[47] ibid paras 439–441 (common interest in protection of commons).

[48] ibid paras 200–225 (treaty obligations; mitigation, adaptation, co-operation).

[49] ICJ Advisory Opinion, paras 427–429 (attribution and relevant conduct).

[50] ibid para 510 (obligations erga omnes).

[51] Separate Opinion of Judge Charlesworth, Obligations of States in respect of Climate Change (23 July 2025 (SIDS testimonies).

[52] ICJ Advisory Opinion, para. 456.